Hope Factory Tour

Few component manufacturers carry the cred and credence of British company Hope. Steve Thomas dropped in on them to see how they’ve managed to stay true to their colours for almost a quarter of a century.

These days it’s rare to see a label stamped on a prime piece of high-end bike kit that reads ‘Made in the UK’. In fact it’s pretty uncommon to find decent gear that’s made anywhere outside of Taiwan or China.

These days it’s rare to see a label stamped on a prime piece of high-end bike kit that reads ‘Made in the UK’. In fact it’s pretty uncommon to find decent gear that’s made anywhere outside of Taiwan or China.

Some manufacturers still make their range-topping items on home turf. Others may source parts from every corner of the globe before assembling them in-house so they can be labelled as, ‘made in the…’ Neither of these is the case with Hope.

Hope is based in a small market town called Barnoldswick in Lancashire; a rough ended and rugged place in the north of England that’s famous for its textile mills. Despite the economic woes as well as relative high labour and production costs, virtually every item bearing the Hope name is and always has been hand made in the UK. They’ve somehow managed to stay true to the principles that they started out with some 23 years ago, and they’re thriving on them too.

Taiwan and China are now firmly established as the epicentres for bike and component manufacturing so why does this privately owned and self-sufficient company choose to make almost all their gear in the UK and how have they remained competitive?

Sales and marketing manager Alan Weatherill speculates, “Maybe it’s a control freak kind of thing, but when you make it yourself you can inspect the product continually. There’s also no R&D wait-time—it’s just there. Also, when the company started out, my brother (Ian Weatherill) really wanted to put something back into the local community, as unemployment was huge in the area.”

He continued, “Overall, manufacturing in the UK it doesn’t really work out to be much more expensive. The guys in China use the same machinery and their raw materials costs are the same, as they often obtain it from the same steel consolidators. Here we have a very skilled and efficient workforce too; our staff can work up to eight machines at a time. They are very productive so the overall labour costs really aren’t that different to what you’d find in China.”

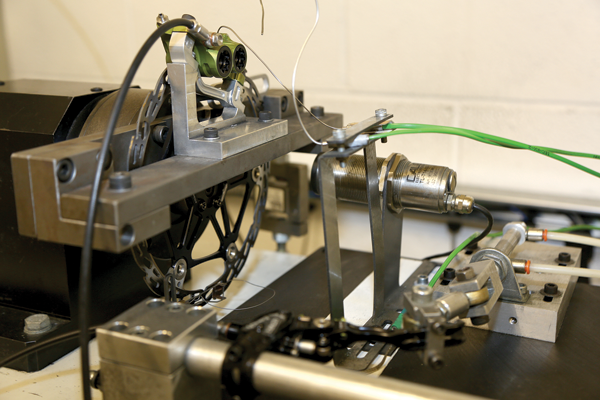

With many bike companies their development and marketing staff spend much of their time commuting between Asia and Europe or the USA, and they also wind up working to tight manufacturing schedules. This isn’t the case with Hope. “Most of the design staff can also machine up a product, so from the conception of an idea we can have a prototype made in no time—it’s really easy for us and everyone gets involved in the design process. For example, when SRAM introduced the XX1 cassette, we had the drawings for the XD freehub body done in a day. A working sample was also made in a day. So within no time we can have a product ready to show and test—we don’t have to go to somebody else to get the job done.”

The whole Hope story began out of necessity, “My brother (Ian Weatherill) and Simon Sharp were not happy with the rim brakes on their mountain bikes. They were both engineers making tools at Rolls Royce Aerospace (who also have a factory in Barnoldswick). Both were into motorcycle trials, so they decided to build some disc brakes for their own use.”

Like any good Lego kit, things went from there; “Because they made the brakes they decided to make the hubs too and they started selling them. This was before disc brakes were well accepted in mountain biking, so the hubs took all of the attention.”

It was a tough time for the manufacturing industry in the UK, but within a couple of years the two partners had put their hubs and brakes into full production and they’ve not looked back since.

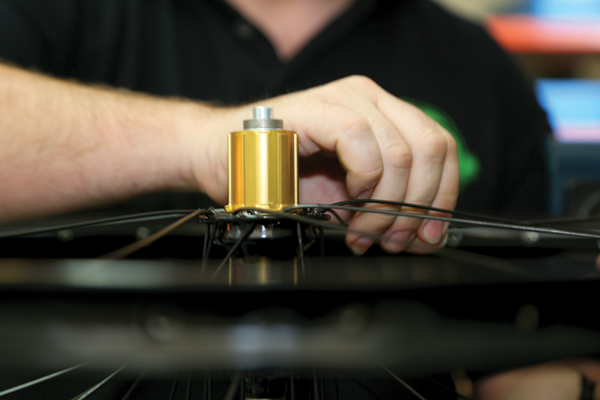

Although it was the disc brakes that inspired the birth of the company, it was the hubs that really established them in the marketplace. “Hubs are still our biggest product,” Weatherill told us, “they are both durable and light with the best quality bearings and seals—we’ve really built our reputation on them.”

“We started with the front hubs for the disc brakes. The rear hubs came next; that was about the time when cassette systems arrived on the scene and it took us a couple of years to perfect the rear hubs. We were machining everything from aluminium, so we also started making skewers, seat clamps, bar-end plugs—basically coloured parts for your bike.”

It’s now rare to see a decent mountain bike without disc brakes but some are clearly better than others. Having been relative pioneers in the area, what do they make of the evolution in recent years? “It seems that most manufacturers try to make the most powerful brakes, but these days we try to balance power with feel. The biggest restriction is the grip offered by your tyres, so it’s not all about power. We used to be the most powerful, but now we aim for power with feel.”

In some situations their approach doesn’t pay dividends; “It can come across negatively in magazines because on a test bench they mightn’t be so powerful, but in reality they are far nicer to use. Ultimately you can always lock up the tyres, but you don’t need to. We do make the downhill brakes more powerful, so that you can use them with one finger.”

Throughout their evolution Hope has carved their own route, often bravely going where other manufacturers dared not. “We don’t tend to look at other bike companies. Instead we look at other industries, maybe looking at different ideas for motorcycle brakes along with other technologies and try to combine them to suit.”

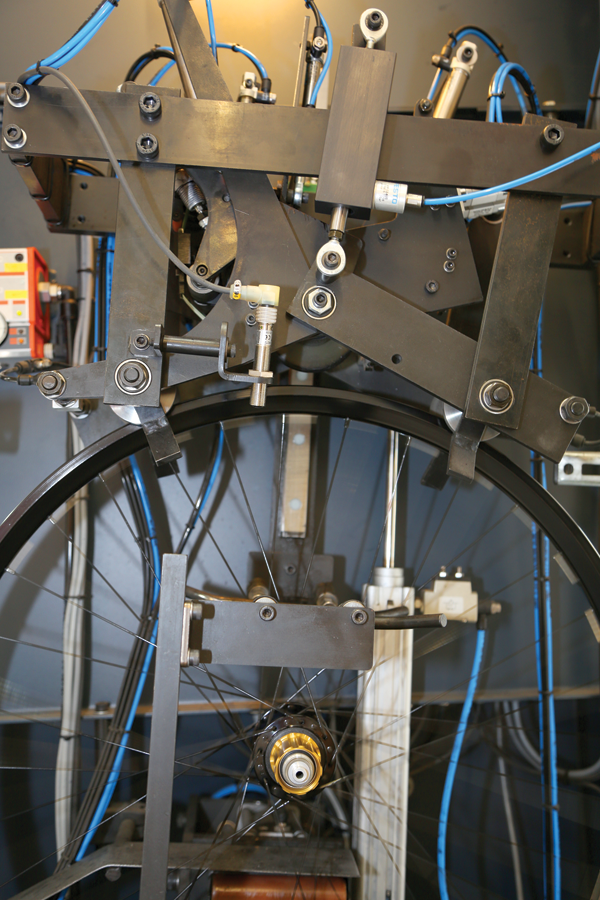

With a full fleet of staff bikes and many leading riders working for Hope, much of the product testing is done in house. “We have always done most of the testing in house, but we have started to put more out to other athletes. If you get a Hope trained employee offering a viewpoint, it mightn’t be the same as someone else—we’re trying to get more varied feedback.”

While Hope makes a broad range of products, you’ll usually only find one item within each product category. “People often ask why we don’t do cheaper and higher end models but we’re not inclined to go in that direction. We prefer to make stuff that works and it costs whatever it costs. Although we do manufacture different brakes, it’s all down to intended use, not price or grade.”

Hope has been long-time supporter of cycling – both road and MTB – yet they have never really shouted it from the rooftops as other companies often do. “At the end of the day we’re engineers who happen to sell bike parts—we are not a marketing company. Perhaps we’ve not made the most of certain marketing opportunities but it works for our kind of style.”

A few years back the company made what was probably their biggest leap in terms of diversification; they moved into the into lighting market. “Once again it was a case of the staff wanting something that didn’t exist. We started playing around with motorcycle lights and batteries, developed our own lights, and then started to sell them.”

Surprisingly, even the lights are largely home made, “Others tend to import plastic housings and other stuff for their lights but we can machine most things ourselves. We have a guy here that designs the circuit boards, but they are made in Southport which is close by, so it’s still all local.”

With wheels also being built on the premises, the Hope Hoops line-up will now include their ‘own brand’ carbon road rims. “While we do build the wheels here, we don’t make the rims or spokes—it’s really not our thing. We’ve now got our own supplier for carbon rims. There are just so many expensive carbon rims that are built with cheap hubs and sold as factory sets, so we wanted to do something with our hubs.”

With many manufactures primarily selling factory built wheelsets these days, you’d assume that the hub market would have slumped. According to Alan, “We thought it would affect our hub business—that’s why we started building wheels. But, somehow our hub business has actually increased. I think it’s all down to the way other people have marketed the concept. Some brands direct all their effort into promoting their built wheels, so you tend to forget that they make hubs. With Hope, you think of our hubs.”

What else can we expect to see coming from Hope in the future? “Well we’re working on cranks. While we currently do single chainrings, we’ll also be working on shifting rings to go with the cranks. We are making a new cassette too—the new product is all drivetrain focused for now. Dropper seatposts are something we should also make, although it may take a while.”

More options in materials may be on the horizon; “We’re also looking at doing carbon fibre in house—that’s another new thing, just simple carbon fibre products.”

While their range has diversified over the years, there have been concepts that didn’t make the cut; “At one stage we started working on a complete bike, it wasn’t that difficult but it was different to what we were used to. We sidelined that one and may look at it again in the future.”

With most of the staff and all of the management riding and racing bikes year round, it’s clear that there’s a down to earth passion and enthusiasm for cycling at Hope. The products they design and build simply aim to make riding more fun—they are practical and committed people.

As for the name, well you might imagine that it was a motto borne from optimism—the long shot of wanting to make something from the rubble of a crumbling industrial economy, but that just wouldn’t be practical enough for these guys. Alan explained, “The company needed a name, and the business was set up in the Hope Mill, hence the name.”

Anthology of Hope

1989 – Business partners in an engineering firm (and trained Rolls Royce Aerospace engineers) Ian Weatherill and Simon Sharp decide they weren’t happy with the performance of the cantilever mountain bikes brakes. Being engineers, and coming from a motorbike trials background, they decide to make their own disc brakes.

The callipers were cable operated and they used screw-on-style rear hubs up front to mount the rotor. Dissatisfied with that, the pair decided to make their own hubs to complement their brakes. This was the beginning of Hope as we know it.

1991 – After two years of designing and making their own hubs and brakes, Hope Technology was formed to make and sell disc brakes and hubs.

1992 – Hope first exhibited their brakes at Interbike in the USA. There were brakes on 14 different show bikes around the halls and at this point they only had 14 sets of brakes! Hope gained a good following for their hubs in the UK where the US imported items were expensive.

1993 – Hope launched the ‘Ti-Glide’ rear hub; one of the first Shimano-compatible aftermarket cassette hubs. It used a titanium central body and a titanium cassette body. It was light and looked cool too.

1994 – Hope introduced their first hydraulic brake. The front mounted via CNC machined adaptors and the rear required custom braze-on mounts.

1995 – The 185mm front disc and ‘Big’un’ hub set was introduced for downhill racing. Hope switch to Kevlar reinforced hydraulic hose at this time.

1996 – Hope introduced their ‘Sport Lever’ with its thumbwheel adjuster. Their ease of use, power and mid-race adjustability saw many pro riders using Hope brakes regardless of sponsorship obligations.

1997 – Hope took their first Grundig World Cup victory with Rob Warner winning in the rain of Kaprun, Austria.

1998 – Hope’s DH4 downhill brake was unveiled at Interbike and the ‘Pro Series’ lever was introduced. They also slimmed down their brake callipers at this time.

1999 – Steve Peat came second in the World Cup Series and won the British National Championship using Hope kit. In the British National Series, all of the top-10 finishers were using Hope brakes. Hope also launched the world’s lightest disc brake system—the XC4.

2000 – Hope launched the ‘Bulb’ hubs. They offered great versatility by allowing either quick release or 20mm thru-axles to be used in the same hub.

2001 – Hope moved back to an open hydraulic system for XC use with their ‘Mini’ brakes and launched their first six-bolt cross-country disc hubs.

2002 – Headsets were added to the range. They featured stainless steel bearings and seals everywhere to keep out the UK water and mud. Small parts were added to the range with bar end plugs and A-headset caps.

2003 – Launch of the Mono 6ti brakes. Using a six-piston calliper it brought multi-piston motorcycle technology to cycling. The Mini and M4 brakes changed to a one-piece calliper; this design now used industry-wide.

2005 – Stems were launched for XC use with freeride versions following.

2006 – Hope took their first foray into lights with the Vision HID. It was one of the most powerful off-road lights at the time.

2007 – Hope launched the first vented disc for bicycles with the ‘Moto V2’ brake. Two LED lights were also launched and wheels were added to the range.

2008 – A four LED light was introduced and their single LED light was revamped. A new mud-proof bottom bracket was also launched.

2010 – Hope expanded into a new factory. This move increased their workspace from 5,600 square metres up to almost 8,000. Aluminium anodising was now done on site.

2012 – New machinery was acquired and Hope now has 52 CNC machines in service.